Post the COVID-19 pandemic, the shift to the online-first retail industry has transformed how people discover and evaluate products. But in categories like cosmetics and beauty products, where decisions depend on how something looks and feels, the digital experience still falls short. Shoppers are often asked to choose a shade or texture without ever trying it in person—a gap that has existed since the early days of e-commerce.

Even though online platforms have come a long way in logistics and personalization, they still struggle to recreate the in-store experience. Shopping for cosmetics online often leaves people guessing. They can’t be sure if a shade will match their skin, how a texture will feel, or whether the product will suit them at all. That uncertainty makes many shoppers pause, which naturally lowers purchase confidence and increases returns. Static photos or basic filters don’t really solve the problem. What’s needed are systems that can better reflect how people actually see and evaluate products in real‑life situations.

This article describes the design and implementation of a scalable Virtual Try-On (VTO) platform built to support online-first consumer behavior. The work highlights real-world engineering decisions, trade‑offs, and lessons learned from scaling computer vision, augmented reality (AR), and AI technologies.

Problem Context in an Online-First Environment

As physical stores became less central to how people discover new products, online channels had to take over experiences that used to happen naturally in-store. Instead of in-store mirrors, testers, and real lighting, shoppers were now relying on flat images and short descriptions—tools that rarely give enough confidence when choosing something as personal as cosmetics. When we studied how people actually used that online experience, a few themes kept repeating themselves:

- Returns were noticeably higher, mostly because the product didn’t match what shoppers expected once it arrived.

- Conversion dipped for face and lip products, where picking the right shade is especially unforgiving.

- People didn’t stay on the page for long, partly because there wasn’t much for them to play with or explore.

- On top of that, the experience varied a lot depending on the device, screen quality, or even network strength.

Taken together, these patterns made something obvious: this wasn’t just about polishing the user interface. The entire system needed a better way to show products realistically.

Limitations of Existing Virtual Try-On Solutions

Most virtual try-on solutions—whether AR filters, in-app try-ons, social media–embedded filters, or simple shade-matching systems—encountered the same set of issues when applied to cosmetic simulations. One of the most significant problems was inconsistent facial detection accuracy. Accuracy often dropped below 70% under non-ideal lighting conditions, on devices with low-resolution cameras, across diverse skin tones, with variations in face shape, or in the presence of facial occlusions.

Most existing solutions rely on generic facial landmark models designed for face detection or expression tracking rather than precise cosmetic simulation. These models typically focus on prominent features such as eyes, nose, mouth corners, and jawlines, while offering limited or no coverage for regions critical to cosmetics, including the upper forehead, cheek curvature, and fine-grained lip contours. Because of these gaps, the cosmetic overlays often appeared misaligned or discontinuous or looked shaky whenever the user moved.

Another fundamental limitation was device dependency. Many AR-based try-on solutions were built and tested on premium phones with high-resolution cameras, dedicated GPUs, and stable frame rates. Performance degraded sharply on mid-range or low-end mobile devices, leading to lag, dropped frames, or complete failure of real-time rendering.

Cosmetic simulation requires more than geometric alignment; it demands color fidelity, texture blending, and lighting awareness. Existing solutions frequently treated cosmetic application as a simple color overlay problem. This approach overlooked key factors such as

- Skin reflectance and subsurface scattering

- Shadowing caused by facial curvature

- Interaction between cosmetic texture and natural skin features

Because these elements weren’t accounted for, the final output often looked flat or slightly artificial, which quickly eroded user confidence. Even small visual mismatches were enough to make shoppers second-guess a shade, something that might be fine for virtual accessories but is a deal-breaker for cosmetics.

Why Existing Models Work for Accessories but Not Cosmetics

Many of the evaluated solutions perform adequately for accessory-based try-ons, such as glasses, hats, or earrings. This is because accessories operate under fundamentally different constraints:

- Accessories are rigid objects with predictable geometry

- Placement tolerances are higher for accessories (e.g., slight misalignment of glasses is acceptable)

- They don’t need to blend with the skin

- Color doesn’t change dramatically with lighting and skin tones.

Cosmetics, on the other hand, behave like part of the skin itself. They flex and shift as the face moves, react to lighting, and look different across skin tones and textures. Generic face detection models do not capture the fine-grained spatial and photometric details required for realistic cosmetic simulation. This mismatch explains why platforms that succeed in accessory try-ons often fail when extended to makeup applications.

Solution Design: Facial Detection and Landmark Model Extension

To address the limitations of generic facial landmark detectors, facial detection and landmark localization were treated as separate stages to prevent error propagation commonly observed in end-to-end pipelines. Face detection was used solely for coarse localization, while all cosmetic placement relied on landmark geometry. Several detection approaches were evaluated, including classical detectors and deep learning–based single-shot models. Lightweight CNN-based detectors with multi-scale feature extraction were selected due to their higher recall under unconstrained conditions such as variable lighting, partial occlusion, and diverse skin tones. Detection models were optimized for robustness rather than tight bounding box precision, ensuring reliable face initialization across heterogeneous devices.

Once a face region was detected, facial landmark localization was performed using an extended landmark model derived from a standard 68-point architecture. Thirteen additional landmarks were introduced in cosmetically critical regions, particularly the upper forehead and lateral face areas, where baseline models exhibited systematic spatial drift. Landmark placement was constrained by anatomical symmetry and facial topology to reduce bias and prevent overfitting. Training data was curated to balance skin tone, age, face shape, lighting conditions, and head pose, reducing demographic bias and improving generalization.

To ensure temporal stability and eliminate visual artifacts during head movement, the system addressed the inherent frame-to-frame noise present in real-time facial landmark detection. Even when detection accuracy was acceptable on individual frames, small variations in landmark positions—caused by sensor noise, lighting fluctuations, and minor pose changes—produced visible jitter in cosmetic rendering. Applying cosmetic effects directly to per-frame landmark outputs amplified these variations, resulting in unstable boundaries and perceptible flickering during motion.

Temporal Stabilization and Region-Based Rendering

Even with improved landmark coverage, per-frame landmark estimates exhibited minor temporal noise that produced visible jitter during motion. To mitigate this, landmark stabilization was formulated as a lightweight state estimation problem inspired by Kalman filtering principles. Rather than applying a full Kalman filter, a simplified recursive estimation approach was adopted, assuming locally smooth facial motion over short time windows.

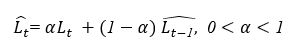

For a landmark position Lt at frame t, the stabilized value ^Lt is given by:

Where ^Lt-1 represents the prior stabilization estimate and α controls the trade-off between responsiveness and temporal smoothness. The parameter was empirically selected to minimize perceptible jitter without introducing latency. Stabilized landmarks were then used to define convex polygonal facial regions corresponding to cosmetic application zones. All rendering operations were constrained to these regions and applied using luminance-normalized blending functions, ensuring geometric continuity and consistent cosmetic placement during head movement and expression changes.

Experimental Methodology and Validation

The proposed approach was evaluated against the baseline 68-point landmark model using a test dataset designed to reflect real-world usage conditions. The dataset included variations in lighting (indoor, outdoor, low-light), device class (high-end, mid-range, low-end), skin tone, facial geometry, and moderate facial occlusions. Performance was assessed using region-specific landmark accuracy, temporal stability metrics, and qualitative rendering consistency during motion.

Quantitative results demonstrated substantial improvements over the baseline model, particularly in cosmetically relevant regions. Table 1 summarizes the comparative results.

Table 1. Quantitative Comparison of Baseline and Extended Landmark Models

| Metric | Baseline (68 points) | Extended Model (81 points) |

| Upper-face landmark accuracy | 68-72% | >91% |

| Frame-to-frame landmark variance | 1.00 (normalized) | 0.55 |

| Observable jitter during motion | High | Reduced by ~ 38% |

| Rendering failures on low-end devices | Frequent | Significantly reduced |

| Cosmetic boundary misalignment | Common | Rare |

In addition to numerical gains, qualitative evaluation showed visibly improved stability and alignment of cosmetic effects during head movement and expression changes. The reduction in landmark variance directly correlated with improved perceptual realism and user trust. These results validate that extending landmark coverage and enforcing geometric and temporal constraints are critical for reliable cosmetic virtual try-on systems operating under real-world conditions.

Observed Outcomes

Deployment of the virtual try-on platform led to measurable improvements across key metrics:

- Increased user engagement and session duration

- Growth in online sales for previously underperforming product categories

- Reduction in return rates driven by improved purchase confidence

- Lower cart abandonment through interactive exploration

- Reduced environmental impact due to decreased reliance on physical samples

Importantly, the platform expanded reach among users who previously avoided online cosmetic purchases due to lack of trial options.

About the Author

Pallab, an Assistant Vice President (AVP), and Enterprise Solution Architect, drives cloud initiatives and practices at Movate. With over 18 years of experience spanning diverse domains and global locations, he’s a proficient multi-cloud specialist. Across major cloud hyperscalers, Pallab excels in orchestrating successful migrations of 45+ workloads. His expertise extends to security, big data, IoT, and edge computing. Notably, he’s masterminded over 30 cutting-edge use cases in data analytics, AI/ML, IoT, and edge computing, solidifying his reputation as a trailblazer in the tech landscape.